The truth about images stored in the eyes of… the dead

For a long time, scientists wondered whether the eyes could store images of our last glances before we die.

And it was not until the invention of the camera that this interesting topic was widely studied.

Failed experiments

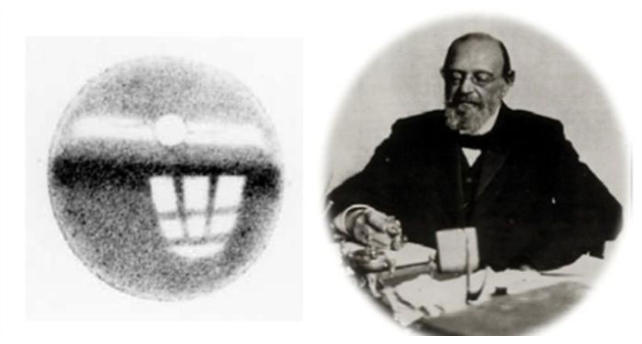

Scientist Wilhelm Kühne saw the picture in the rabbit’s eye as it died.

In 1876, German physiologist Franz Christian Boll discovered rhodopsin – a photosensitive protein in the rod cells of the retina, which acts like nitrate on a camera lens, bleaching when exposed to light.

Unfortunately, Boll’s life ended prematurely at the age of 30 due to tuberculosis, preventing him from doing further research. However, these findings were enough to convince the scientific community that changes in rhodopsin play an important role in the functioning of vision.

After Boll’s death, one of his admirers, the German physiologist Wilhelm Kühne, took up the discovery with “burning enthusiasm.” Kühne began experimenting with a variety of animals, removing their eyes very soon after death and using various chemicals to fix images on the retina.

The following story by biochemist George Wald, who won the Nobel Prize in 1967 for his work on visual pigments, describes one of Kühne’s most successful experiments with a rabbit:

An albino rabbit was tied up, facing a barred window. From this position, the rabbit could see only a gray, cloudy sky. Its head was covered with a cloth for a few minutes to allow its eyes to adapt to the dark, that is, to allow rhodopsin to accumulate in the rod cells of the eye.

The animal was then exposed to light for three minutes, then decapitated, the eyes removed, and the posterior half of the eyeball containing the retina placed in alum solution for fixation. The following day, Kühne produced a photograph of a window with a clear pattern of iron bars imprinted on the retina of the rabbit’s eye.

Kühne had been eagerly anticipating performing this technique on human subjects, and in 1880, an opportunity presented itself. On 16 November, the condemned man Erhard Gustav Reif was sent to the guillotine for murder in the nearby town of Bruchsal.

Ten minutes after the execution, his eyes were extracted and delivered to Kühne’s laboratory at the University of Heidelberg. The optograms that Kühne made of Reif’s eyes do not survive, but a sketch of what was seen on Reif’s retina appeared in Kühne’s 1881 paper “Anatomical and Physiological Observations on the Retina.”

It does not resemble anything a condemned man would have seen at the moment of death. However, some have suggested that the sketch resembles the blade of a guillotine, although the victim could not have seen it because he was blindfolded. Others have suggested that they may have been the steps leading to the gallows. Kühne offered no explanation for the images.

Physiologist Franz Christian Boll discovered the photosensitive substance rhodopsin, which helps the eye function like a camera.

Prospects for forensics?

Although Kühne did not obtain a clear optical image of a human eye, the idea that the deceased retained a final image in the eye continued to hold sway in the popular imagination at the time.

When it was suggested that retinal scans could be obtained from murder victims to help identify murderers, the French Society of Forensic Medicine asked Dr. Maxime Vernois to conduct a study to test the feasibility of using retinal scans as evidence in murder trials. Vernois dissected the eyes of 17 animals he had killed, but discovered nothing.

Despite the unsuccessful experiments of Kühne and Vernois, other researchers persisted in photographing the eyes of murder victims in the hope that the images might help solve criminal cases. Detectives around the world have proposed using the technique on murder victims.

Rumors of the dead retaining their final images in their eyes are so widespread that some murderers have attempted to destroy the eyeballs of their victims after they have killed them.

By the early 20th century, investigators had given up hope that optics could be developed into a useful forensic technique. However, in 1975, the police in Heidelberg, Germany, asked scientist Evangelos Alexandridis of the University of Heidelberg to use modern scientific techniques, up-to-date knowledge, and advanced equipment to re-examine Kühne’s experiments and findings.

Following Kühne’s example, Alexandridis attempted to produce some high-contrast images from rabbit eyes. However, he concluded that optics had no potential as a forensic tool.

And this was the last serious scientific study of optics to produce images from dead human eyes. Nevertheless, the concept has endured in science fiction and detective fiction.

The famous science fiction writer Jules Verne also maintained the belief that optics had potential in crime investigation in his 1902 novel “Les Frères Kip.” Over the next hundred years, the idea would appear frequently in literature and media. The 1936 film “The Invisible Ray” featured a scene in which Dr. Felix Benet, played by Bela Lugosi, uses an ultraviolet camera to photograph the eyes of his deceased victims.